Title: MSFS Legacy for the Future: Alison Chen (MSFS ‘20)

This story is part of our MSFS Legacy for the Future series profiling members of the MSFS community who have made, or are poised to make, important contributions to international affairs. Through our Legacy for the Future campaign, you can support MSFS scholarships for talented students and ensure that the leaders and innovators of the future are given the skills and opportunities they need to meet the global challenges of tomorrow, today. Make your contribution to MSFS Legacy for the Future now.

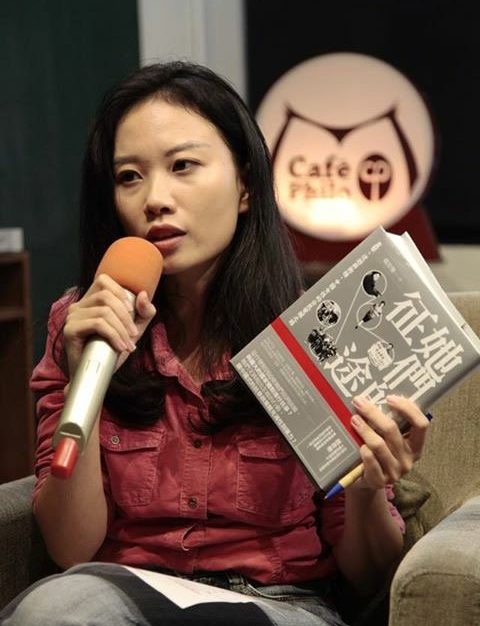

Alison Chen (MSFS ‘20) set herself two goals to achieve before her thirtieth birthday: write a book and study abroad. In 2017, at age twenty-six, Alison published Her Battles (written under the name Zhao Sile), a book exploring the history of post-1989 activism in China through the lens of women’s experiences. Approximately a year later, she arrived in Washington, D.C. to start her degree at the Master of Science in Foreign Service program at Georgetown University.

Alison’s ambitious aims reveal her drive to build a successful career but they are also a reflection of the motivation that has defined her journalistic work for close to a decade: to raise awareness of civil society and social and political activism in mainland China. While Alison has won numerous professional awards for her work (she has received the Hong Kong Human Rights Press Award six times and is the winner of two Society of Asian Publishers Awards, among the top honors for covering Asia), she is quick to remind her supporters of what is at stake in the stories she covers. In 2016, she received the Hong Kong Human Rights Press Award for a story on the Chinese government’s crackdown on domestic NGOs. During her acceptance speech, she told the audience that she was not sure how to feel about her award. “My stories are derived from others’ suffering,” she said.

Alison’s work chronicles the experience of civil society activists in mainland China whose critiques and actions against powerful institutions are often met with censorship, sanctions, imprisonment, and violence. In her time as a journalist, she has carried out investigative reports into the anti-corruption protests in the village of Wukan, the 2015 detention of prominent Chinese feminists, and most recently the Chinese state’s use of exit bans to put pressure on suspected dissidents. Much of her reporting focuses on women and the Chinese feminist movement, a perspective that she feels is often overlooked in coverage of Chinese civil society and social movements.

Alison’s first foray into professional journalism came in 2011 when she was in her third year at university and was participating in an exchange program in Taiwan. An editor for iSun Affairs Weekly Magazine—an independent current affairs online magazine run by mainland journalists based in Hong Kong—approached Alison to write for the title after coming across some articles she had written about transport infrastructure and tree removal in Nanjing. Impressively for a new reporter, Alison was responsible for covering Taiwan’s presidential elections and even managed to question the presidential incumbent Ma Ying-Jeou.

After finishing her studies in Taiwan, Alison returned to mainland China where she covered high-profile anti-corruption protests by villagers in Wukan in Guangdong province. Locals were protesting corruption relating to land sales perpetrated by members of Wukan’s village committee and successfully pushed for new and democratic local elections. The reporting climate Alison experienced on her Wukan assignment was vastly different from the work she had done in Taiwan. She told Hong Kong Free Press, “You couldn’t tell where it was safe or dangerous, you couldn’t tell what would happen tomorrow.”

While covering the Wukan protests, Alison noticed that the important role of women activists in the village was generally overlooked in other press reports. This is often typical, she says, of coverage of Chinese politics, especially activism and social movements. This reality is one of the reasons why so much of her work explores the experience of Chinese women in these spheres. “I’m interested in politics but on-going elite politics is too implicit in China,” she says. “Reporting social movements is another way to look into politics and authorities in China. Men’s stories [within social movements] tend to be very typical and similar. Women’s stories are untold, surprising, and inspiring.”

iSun Affairs closed down in 2013, the year Alison graduated, so she joined the team at Feminist Voices, a media advocacy group supporting women’s rights that has since been banned in China . Feminist Voices was committed to the abolition of the Custody and Education (C&E) system, which allows Chinese police to detain sex workers and their clients without trial for up to two years, and Alison wrote 320 applications to the Chinese government asking for disclosure information related to C&E. When all of them were rejected, she sued the government for refusing to release the information.

Her relationships with feminist and civil society activists in mainland China also meant that Alison’s advocacy was sometimes deeply personal. In 2015, police arrested five of Alison’s friends on International Women’s Day. Known as “The Feminist Five”, the women had been planning a public protest again sexual harassment. Around the same time, Alison’s former husband, an NGO employee working on legal issues, was detained by the government. His family suspected that the state believed he had connections to the Occupy Movement in Hong Kong. Alison devoted herself to freeing her loved ones, giving interviews with the media, hiring lawyers for her husband, and writing about the arrests.

Alison says that while it can be difficult to scrutinize how her connection with and sympathy for activists affects her perspectives, she is committed to writing objectively about their work. “I see my work as a form of activism. Not through writing anything about Chinese activism that is better than its reality but by telling the truth.”

Much of Alison’s work was dedicated to telling the stories behind domestic politics and protests on mainland China. However, a desire to understand the implications that international relations and Western foreign policy had for China’s civil society culture led her to apply for international affairs graduate degrees in Europe and the United States. As the top-rated master’s program in international affairs, MSFS was the obvious choice. Thanks to several scholarships, including the Kellen Scholarship awarded by the MSFS program, she enrolled in her first semester in the fall of 2018. Her classes helped her to gain a deeper understanding of how international relations affect the lives of citizens in China. “Listening to and participating in the discussions [at MSFS] has brought me much closer to the reality of U.S. foreign policy and its effects on Chinese politics,” she says.

Alison has continued her reporting while studying, although her work has been directed more toward English-speaking readers and the Chinese intellectual community than before. This, she says, is due in part to her desire to focus more on her studies as well as greater crackdowns by the Chinese state on censored media. “I’m not communicating with a Chinese audience as much now and the ways I did before would not work now. Communication is much more restricted than before. Some Chinese people get over the Great Firewall and follow me on Facebook and Twitter and read my work. But, I’m focusing more on improving my analysis and understanding of Chinese issues in a global context.”

While at MSFS, Alison has published multiple stories and papers in English, including for The Georgetown Journal of Asian Affairs, The Women’s Media Center, and Foreign Policy. She has also spoken at events and conferences across North America. Last semester, Alison interned at the Wilson Center’s Asia Program, where she wrote analysis pieces for the think tank. While she is learning a lot, Alison admits that being part of D.C. policy discussions as they relate to China has not always been heartening but that it has strengthened her resolve to advance Chinese civil society and the community’s understanding of Chinese international politics post-graduation. “I now understand that U.S. policy-makers won’t help Chinese civil society if Chinese activists cannot critically improve their capacity, and this won’t happen in the current circumstances,” she says. “Studying in the U.S. can make me more pessimistic about China’s future but it is also a motivation for me to devote more to Chinese civil society.”

Alison plans to split her time between mainland China and the U.S. after graduating and to support the efforts of activists advocating for democracy and the advancement of human, and specifically women’s, rights. This is not without risk. Many of Alison’s friends and colleagues have been imprisoned or forced to live elsewhere due to their work. But her commitment to those calling for greater democracy, equality, and justice in her home country is unwavering. “Just do whatever you can,” she says. “Until the day you can do no more.”

Support more students like Alison Chen to come to MSFS. Donate to our MSFS Legacy for the Future campaign today.