Title: MSFS Legacy for the Future: W. Gyude Moore (MSFS ‘09)

This story is part of our MSFS Legacy for the Future series profiling members of the MSFS community who have made, or are poised to make, important contributions to international affairs. Through our Legacy for the Future campaign, you can support MSFS scholarships for talented students and ensure that the leaders and innovators of the future are given the skills and opportunities they need to meet the global challenges of tomorrow, today. Make your contribution to MSFS Legacy for the Future now.

Google W. Gyude Moore’s (MSFS ‘09) name and you will quickly discover that he is one of the foremost experts on African infrastructural development. As Liberia’s former Minister for Public Works and Head of the President’s Delivery Unit (PDU), Moore oversaw public sector investment programs that spent billions of dollars on road, power, port infrastructure, and social programs in the country after its civil war. He has written extensive articles and given numerous expert interviews on everything from Huawei’s role in Africa’s telecommunications capacity to how low and middle-income countries can protect their infrastructure from natural disasters. In a popular TedX talk where he argues that building resilient highways across Africa can economically transform the continent, Moore admits that he has been “obsessed with” the power of roads to usher in what he calls the “Brown Revolution” for nearly a decade.

Though Moore’s online presence is associated with paved highways, cellphone towers, and weather-resistant building materials, the broader aim of his work is toward something much less tangible. He believes that services, infrastructure, and material goods are symbols of a functioning state that boost public confidence in elected governments. And, as he knows from his own experience in government after the Liberian Civil War, when material infrastructure is lacking or damaged so too is trust between governments and their people.

“When people imagine war, it’s usually the loss of lives and destruction of the physical built environment that come to mind,” he says. “And that’s for good reason. More than 200,000 Liberians died in the war. Physical infrastructure was both directly destroyed and indirectly eroded by disuse and lack of maintenance. But there was also erosion of the structures of governance. The state’s ability to perform its basic functions—provide security and social services, collect taxes, provide justice.”

Rebuilding after civil war

Rebuilding the state, its legitimacy in the minds of the Liberian people as well as its systems and structures, was Moore’s key goal in his post-war work in government. Under his leadership at the PDU, Liberia built up its seaports, airports, roads, and crucial bridges and qualified for a MCC Compact. As Minister for Public Works, Moore instituted The Road Fund Act to collect road user fees to repave Liberia’s roads with cement and introduce regular road maintenance across the country.

In post-conflict settings, Moore says, it is tempting to prioritize many different development projects. However, lack of time, expertise, and money often make it impossible to deliver on numerous programs. Instead, Moore chose to create a compact list of priorities for infrastructural development in Liberia that were deliverable and the successful completion of which would build up public trust in the state. “In a democracy, this [approach] will invite criticism and other political actors will look to exploit it,” he admits. “But spreading limited resources over a priority list of twenty or so items guarantees that little actual progress will be made in any one area.”

The importance of perception underpins much of Moore’s development philosophy. Since leaving the Liberian government, he has argued that branding aid with the logos and slogans of international governments and aid agencies can undermine the social contract between local governments and their citizens. And perception, he maintains, explains much of African states’ embrace of Chinese development investment and partnerships, despite Western anxieties about debt traps and cybersecurity issues. In an interview with CTGN, Moore outlines how narratives of China’s historical engagement with Africa play an important role in establishing successful development programs. These narratives emphasize early mutual trade between China and Africa, post-colonial solidarity in the twentieth century, and China’s willingness to invest in projects that have been rejected by Western and international entities. These “stories of development” frame Africans as partners with Chinese institutions, as opposed to beneficiaries of Western aid. As Moore told CTGN: “The West looks at Africa as a place to help with development and China looks at Africa as a place to do business. So where the West saw an unstable place, China saw an opportunity.[…]Politics is largely about perception. Sometimes perception trumps substance.”

Building experience through MSFS

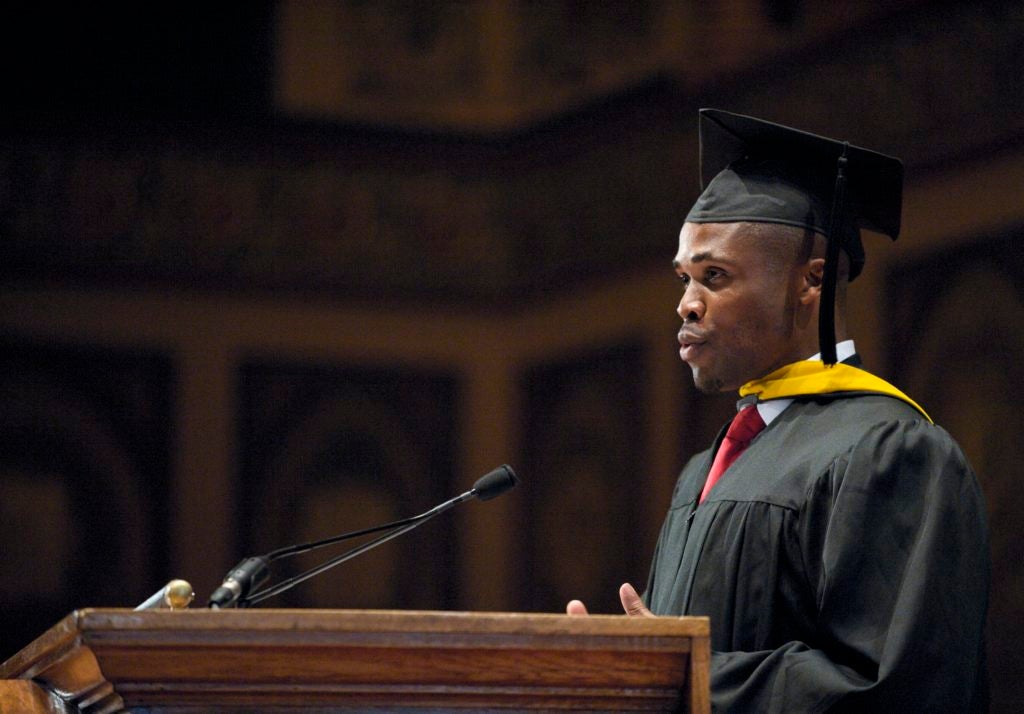

The power of narrative has been important in Moore’s own life, too. As a teenager, his family fled Liberia to escape the war. His mother had recently given birth to twins, one of whom did not survive the journey. In the refugee camp where the family ended up, Moore contracted dysentery and became gravely ill himself. As he told his MSFS classmates during an address to the graduating class of 2009, his own story is a testament to inherent human potential: “It doesn’t require much creativity or imagination to appreciate the vast chasm between the child who lay dying in a refugee camp and the man who is delivering this address today. Just because a person is in one place today, that doesn’t mean that’s where he’s going to end up. I want you to remember that.”

A drive to change his own narrative helped Moore get through the difficult experiences he faced as a refugee. As he explained to CTGN, as a teenager he vowed that he would become a “big man” to alleviate the suffering of other Liberian families. He was determined to gain the skills and experience he would need to take on a leadership position in his home country. He excelled academically and achieved the grades to study Political Science at Berea College, before going on to get his graduate degree from MSFS.

Moore says that the lessons he learned from day one at MSFS remain valuable: “I remember an exercise from my orientation when [MSFS Professor] John Kline drove home the point that some of us would end up in positions of power and it was incumbent on us to take into account those people who had no power. That exercise stayed with me throughout my career.”

Little did he know how soon he would be applying Prof. Kline’s lesson to real government experience. One year out of grad school, Moore was appointed Senior Aide to the Office of the President in Ellen Johnson Sirleaf’s administration. By 2012, he was Head of the President’s Delivery Unit. MSFS, he says, helped him prepare for the leadership positions: “The program equips our students to enter the world, in governments, businesses, and non-profits, prepared to contribute from day one. I remember starting in the President’s office in Liberia and feeling like the circumstances were familiar, even though it was my first time [in government]. MSFS does really well preparing students for the stakes involved.”

Tackling Liberia’s Ebola outbreak

In 2014, Moore was appointed Minister for Public Works. It was the height of the Ebola outbreak in Liberia. Just months before his appointment, Moore had sent a letter to friends and colleagues around the world spelling out the gravity of the situation facing the country. He described one family in which both parents had died from the disease and both children were succumbing to its effects. “It’s hell here,” he wrote. “We can’t do this on our own. Not even on our best day.[…]We need help. We really do. We are running out of time.”

Moore helped to convene the Presidential Advisory Committee on Ebola (PACE), a group of senior government officials and international partners dedicated to tackling the outbreak. PACE included representatives from the Chinese and United States governments and the European Union. Moore points to PACE as an example of how multiple international partners need not compete in the development space but can work together to achieve successful outcomes. In May 2015, the World Health Organization declared Liberia Ebola free and credited innovations such as PACE with bringing about this “monumental achievement”.

Looking to the African future

Today, Moore is a Visiting Fellow at the Center for Global Development where his research tracks the channels of private sources of finance in Africa, the rise of China and its expanding role in the continent, and Africa’s response to these changes. When questioned about what he thinks will be the biggest issue facing development in the next twenty years, his answer is unequivocal. “Africa will come to define the challenges of development over the next two decades,” he says. Automation is canceling out the benefits of the continents’ large population and climate change and limited capacity for preparedness for natural disasters and pandemics is leaving communities vulnerable to shocks. However, despite these predictions, Moore is hopeful that, as during the Ebola crisis, African governments can work alongside multiple international partners to meet these future challenges. And, as he looks toward this future, he is confident that MSFS will continue to provide talented new leaders with the skills and experience he continues to rely on professionally: “Governance is important, regardless of sector. Policies have consequences and, in a complex policy environment, the responses are no longer clear-cut. MSFS attempts to develop the right mix in its students. I am a product of this process.”

W. Gyude Moore is an MSFS Advisory Board Member. Support MSFS to continue to produce international leaders like W. Gyude Moore. Donate to our MSFS Legacy for the Future campaign today.