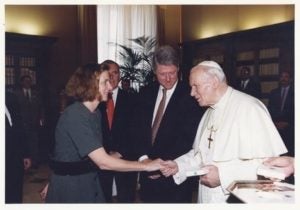

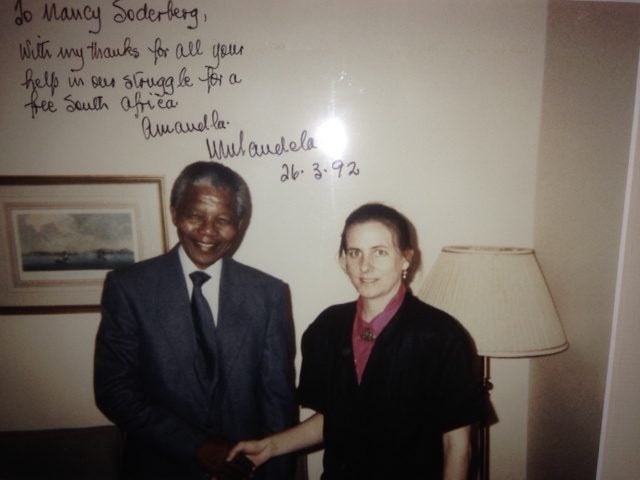

Over the past three decades, Ambassador Nancy Soderberg (MSFS ‘84) has been at the heart of decisions related to many of the most critical questions in U.S. foreign policy. In 1993, she became the first female Deputy National Security Advisor, advising President Clinton (SFS ‘68) on U.S. policies that were influential in ending the decades-long conflict in Northern Ireland known as The Troubles. She was also among the first proponents of tracking Osama Bin Laden as a financier of terrorism.

In 1997, Soderberg was appointed by President Clinton as the United States’ alternate representative to the United Nations. She played an important role in the Security Council, where she negotiated key UN resolutions relating to the Middle East and Africa.

However, when her career was beginning, Soderberg had planned to work in international development. “When I started out at MSFS, I wanted to be a development economist working on Africa,” she remembers. “You don’t really know what you want to do when you first start out in grad school.”

Soderberg credits a particularly memorable class at MSFS with changing her career trajectory and leading her to some of the top positions in US foreign policy. “I was studying development economics but I decided to take [former Secretary of State] Madeleine Albright’s class on foreign policy. She had us all over for dinner and she turned to me and said, ‘I think you should go into politics and work on a campaign.’ My reaction was ‘What?’ I didn’t even know if I was a Democrat! I didn’t know anyone who’d worked in politics. But I thought about it and finally said okay, I’ll try it.”

She decided to use MSFS internship opportunities to explore multiple sectors. The program requires all students to do at least a one-semester long internship before they graduate. Through Georgetown connections, Soderberg interned at USAID, Brookings, and UNDP, experiences that allowed her to discover her true passion for foreign policy. “Internships are so important,” she says. “If I hadn’t done them, I’d be off somewhere doing development. Which would have been fine but I would not have the career that I absolutely love.”

Breaking into foreign policy

Sec. Albright helped Soderberg find her first job working on Walter Mondale’s 1984 presidential campaign. They would later work together on the presidential campaigns of Michael Dukakis and Pres. Bill Clinton. Sec. Albright’s mentorship was transformational for her, she says. “She [Sec. Albright] fundamentally changed my life.”

Post-graduation, Soderberg found herself working with some of the most prominent figures in U.S. politics. “That’s what MSFS does for you!” she laughs. One of her earliest jobs was in Sen. Ted Kennedy’s office as a foreign policy advisor. As a 24-year-old woman, her presence at meetings sometimes surprised her older, male colleagues. “I was usually the only woman in the room and I was often mistaken for somebody’s secretary or translator,” she remembers. “Several times Sen. Kennedy had to stand up and tell people I was his foreign policy advisor. Thankfully, the role of women in foreign policy has changed. We don’t have parity yet but now women have much more of a presence in leadership, premierships, parliaments, and as negotiators.”

Her work with Sen. Kennedy would stand her in good stead when, in 1993, she was appointed as Clinton’s Deputy National Security Advisor. His campaign had made finding a solution to The Troubles in Northern Ireland a key plank of Clinton’s foreign policy platform. The Irish-American connections Soderberg had amassed during her time on Sen. Kennedy’s team would become invaluable to realizing this ambition for the new administration.

Bold steps in Northern Ireland policy

While violence associated with The Troubles—a sectarian conflict pitting majority-Protestant unionists supporting continued Northern Irish union with the United Kingdom against majority-Catholic republicans who desired reunification with Ireland—continued to erupt in the early nineties, Clinton and Soderberg believed that the appetite for peace on both sides was growing. Crucially, Soderberg realized that, as a significant portion of funding for the republican paramilitary organization the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) came from the Irish diaspora community in the U.S., the United States could become an important peace broker in Northern Ireland.

In 1994, the Clinton administration took the bold and controversial step of issuing a U.S. visa to Gerry Adams so that he could attend a Northern Irish peace conference taking place in Manhattan. As the leader of the political party Sinn Féin, which had close connections to the IRA, Adams was listed as a terrorist by the British government, a key U.S. ally. Soderberg admits that while, initially, she cautioned Clinton against such a move, the administration “decided quickly that [reaching out to the IRA] could be a win-win strategy. We realized that if the President stuck his neck out and was able to achieve a ceasefire that was a win for everybody. And if we stuck our neck out and it failed it would give us a lot more power to convince Irish America to pull back from its heavy funding of the IRA.”

Although a solid IRA commitment to peace talks did not emerge from the New York conference, Soderberg says that their efforts to reach out to the IRA helped to position the United States as an honest broker that could reach out to the republican paramilitaries as well as its long-time ally, the United Kingdom. “An honest broker was needed,” she says. “The British would come to us and ask ‘can you guarantee that the IRA will do x, y, and z?’ and we could say ‘No, but here’s what they told us and we don’t think they’d lie to us’ and vice versa. We could help them talk to one another.”

Moving toward peace

Northern Irish peace talks began in 1997 and the Good Friday Agreement establishing a power-sharing government comprising both sides was signed in April 1998. A major milestone for peace, the Agreement is often associated with signatories such as Irish Taoiseach Bertie Ahern and British Prime Minister Tony Blair. However, Soderberg is keen to stress the importance of the ordinary communities that helped to bring about peace.

Women advocates for peace in Northern Ireland were vital to the process, she argues. “In peacebuilding, the role of women is absolutely critical,” she says. “The women of Northern Ireland understood the need for peace more than the men did because they bore the brunt of it. They were the single mothers and they were the ones who had to raise their kids on their own when their husbands were in prison.”

Equally important, claims Soderberg, was the large Irish diaspora in the United States. “There were many millions more Irish Americans than Irish living in the Republic of Ireland and those who were British citizens in the North,” she says. “The insights we would get from Irish Americans on what the IRA was thinking was better than what we got from the British government. In the many conflicts the U.S. is involved in, we often have American citizens in large diaspora communities who have a direct interest in those conflicts. They are willing to help their own governments solve problems and they have a wealth of knowledge and context.”

The importance of MSFS

Today, Amb. Soderberg is concerned about new threats to peace in the region, especially the implications that Brexit could have. Earlier this year, alongside a number of leading Irish Americans, she signed a letter to Prime Minister Theresa May and Taoiseach Leo Varadkar requesting that they protect the Good Friday Agreement at all costs. She says that she is “deeply concerned about the implications a thoughtless Brexit process will have for the Good Friday Agreement. The British government needs to recognize its fragility and make sure they don’t take actions with Brexit that undermine it.”

Her fears for enduring peace are also global in scope. “The world, all of a sudden, is more dangerous and complex,” she warns. “And the U.S. brand has eroded over time through our focus on big-power politics, instead of on individual human rights, and through the rejection of some of the international agreements we made.”

Increasingly complicated international relations make the MSFS program’s commitment to producing ethical, creative, and service-oriented global leaders all the more important, she says. “Government decisions, world decisions on the future of our planet and of humanity are made by human beings. If you have well-trained ethical people who care about changing the world for the right reasons, they can make a true difference.”

She knows from experience that working in foreign policy can be tough but says that her training at MSFS enabled her to make progress in seemingly unsolvable conflicts from within a large and bureaucratic government. “People’s inhumanity is just below the surface and can emerge with frightening rapidity. MSFS trains future leaders to not only challenge the status quo but also how to work a bureaucracy to push a policy through very reluctant old think. It’s not easy. The static forces of the status quo can overwhelm policymakers. That’s where the skills you learn at MSFS are critical.”